MIX MAGAZINE

Knitting Memory

by Katy McDevitt

issue 32.1 2007

To be honest, I’ve been trying to write this essay on the work of Toronto-based sculptor Lynn Jackson for ages now. I keep structuring the damn thing to be a tidy, polite, well-behaved little enterprise. But that can’t be the form it takes because Jackson’s work makes me shiver and shudder, it makes me gasp and flinch, it makes me want to be held in your arms.

What is her work about? It’s about connection and disconnection, body and not-body, past and present, about unification and separation, location and displacement. It’s about to-hell-with-a-ramrod-spine-

Childhood is a dangerous place and a painful place, realities a lot of North Americans don’t much like to acknowledge. Kids’ books that deal with “difficult” subject matter ignite shitstorms of controversy because as a culture we tend to want to gloss over the many ways in which childhood is about powerlessness and vulnerability, about hurt and sadness and fear and anger. I reject that glossing-over, I reject the insistence that childhood is only—or even mainly—idyll and, judging by her artwork, so does Lynn Jackson.

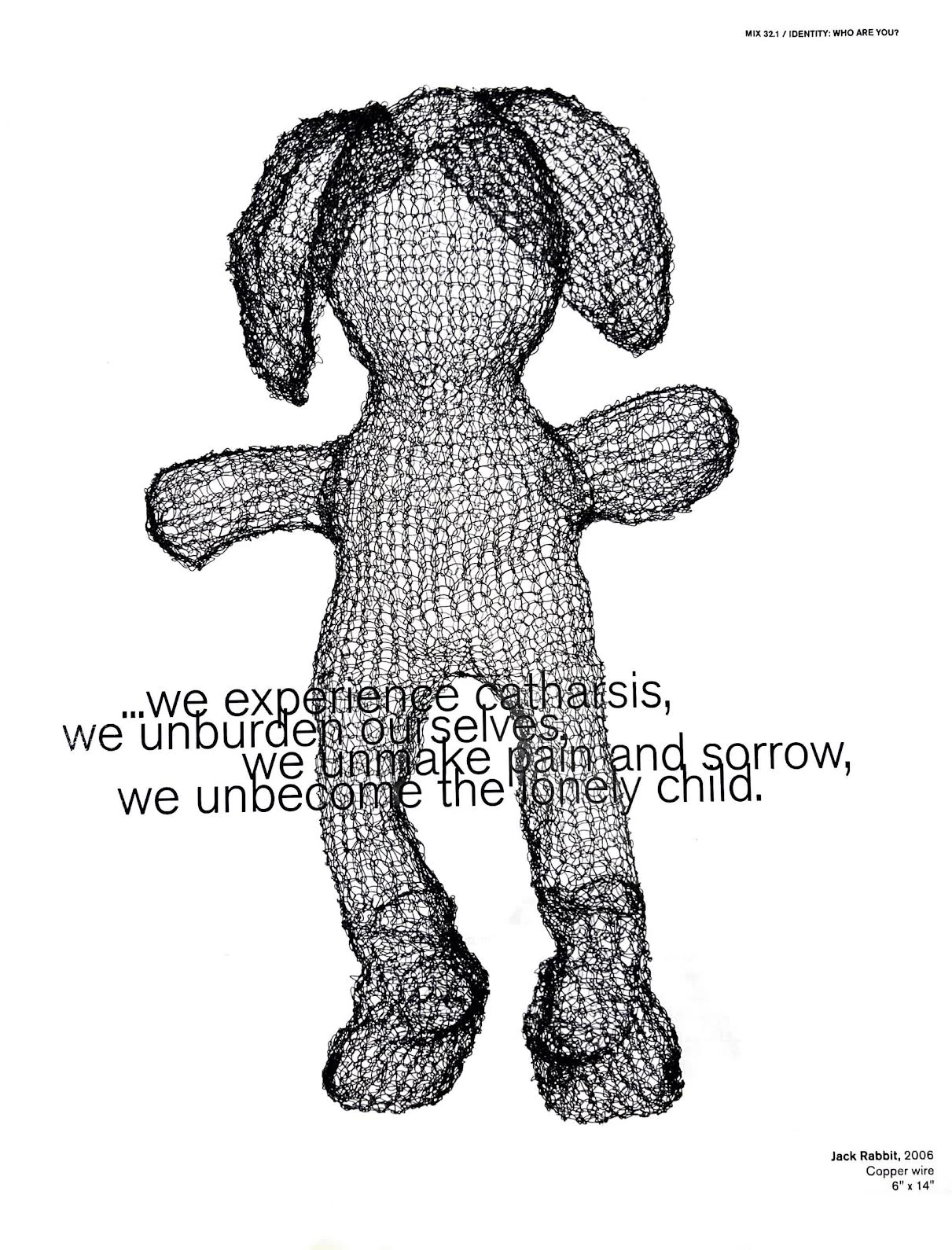

There’s a real challenge to looking at sculptures like Plastic Underpants or New Born Hat or Elephant because they dare us to feel our feelings, something it seems that more and more of us are disinclined to do in this overmedicated culture. But, as Jackson says, “My work compels others to recall their own childhood memories, with the pieces acting as triggers and giving viewers permission to recall their own childhood sadness, loss, happiness, and frailty.” Just as the artist’s sculptures are a making, a rendering concrete of memory, they are also an invitation for viewers to unmake, to unbecome. Through recollection, by allowing ourselves to truly feel our feelings—the good, the bad, the ugly—we experience catharsis, we unburden ourselves, we unmake pain and sorrow, we unbecome the lonely child. Jackson’s work propels us to a place of not-hiding and not-silence, a place where, if we refuse to turn away, we can acknowledge and name the hard moments of childhood, and in that acknowledging and naming, let them go. And there too is one of the strengths of this work: the viewer may be pulled apart emotionally but that happens preparatory to being made more whole, to being knit back together after the damaged bits have been unravelled. It’s not for the faint-of-heart, this artwork, because it presses for a level of emotional engagement that can be very daunting: to be truthful with oneself about childhood is to court pain.

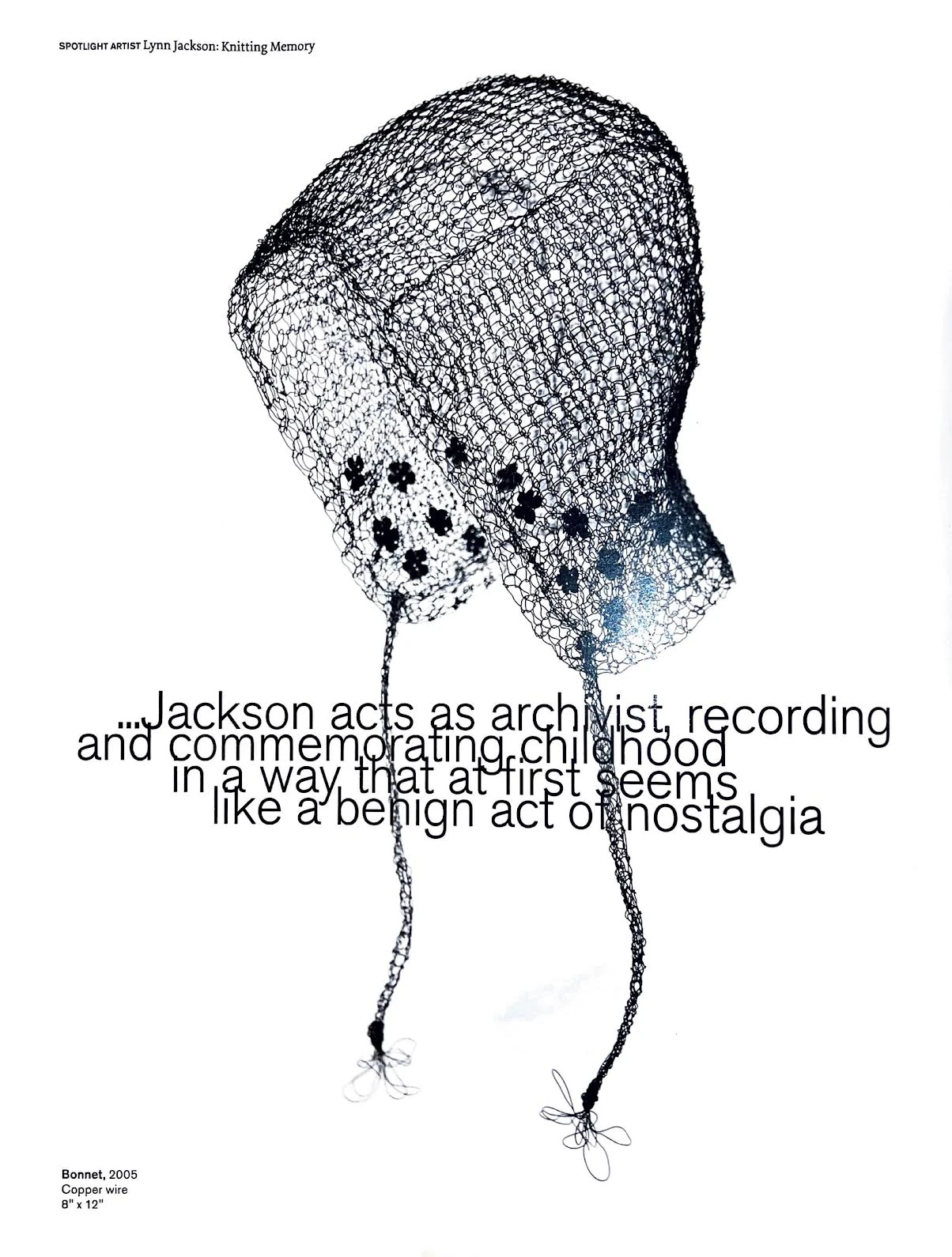

The fact that this work requires bravery of its viewers makes perfect sense, of course, because this is brave work, not only for its exploration of some of the darker corners of childhood but also for its assertion that the “domestic” act of knitting can be and is a valid means of creating art. The trivializing of the feminine is a longstanding tradition within artistic circles and although knitting and other textile arts have found favour within gallery and museum settings in recent years, there is still a tendency in some milieux for such work to be denigrated as something less than Art-with-a-capital-A. So it’s a heady business to see the title of “artist” claimed by a woman who employs a traditional sculptural medium—metal—but who uses a non-traditional technique—knitting—to manipulate it. There is both an honouring of tradition and a breaking with it at play here, a celebration of the domestic and a claiming of the artistic. It’s just that sort of duality that makes Jackson’s work carry so potent an emotional charge.

In the end, I see Lynn Jackson’s sculptures as being linked to Mary Margaret O’Hara’s singing and Louise Lecavalier’s dancing. All three women operate from a place of true-to-selfness, a place of fearlessness and risk-taking, and each artist makes unnerving, thrilling, painful demands of her audience. Rise to the challenge, I say, because to do otherwise is to never become your own true self.

Photo by James Cook